Tom Paine's Bridge

By Patrick Sweeney

Thomas Paine (1737 - 1809) is rightly known for his political writings, particularly Common Sense (1776) which influenced America's bid for independence, and Rights of Man (1791) which gave heightened theoretical backing to the French Revolution and republican ideas. As a man with an analytical mind, his interests overlapped science and politics, providing an example of how rational thought could contribute to the advancement of mankind on this often confused world.

Portrait of Thomas Paine. Engraving by William Sharp after George Romney, 1793.

© National Portrait Gallery, London.

He lived during the age of The Enlightenment, a period that saw a flowering of new and inquisitive thinking about all aspects of life, from philosophy to science, including natural history, economics, engineering, manufacturing and politics. His restless and inquiring mind made him fully part of this revolutionary age. Even though he never gained the success or financial security of his rich contemporaries and friends who dominated intellectual life, he enjoyed all the discussions of the age with relish, and contributed more than most, corresponding with people like George Washington and Benjamin Franklin.

However, he is less well known for his ambitions in engineering, particularly bridge building, which he saw as a symbol of uniting forces within the modern age. It may perhaps have been his boyhood training as a stay maker (stays were women's corsets frequently made from the stiff but flexible whalebone called baleen) that gave him an interest and understanding of engineering. But of most importance is that fact that he saw the revolution in engineering during the eighteenth century as parallel to the much needed revolution in politics and society.

In the year 1779 he would have been aware that a new and revolutionary Iron Bridge had been constructed at Coalbrookdale over the River Severn, the birthplace of smelting iron and the heartland of the industrial revolution. It was the first major bridge in the world to be constructed entirely of iron, and it stood as an astounding beacon of the new industrial age, so much so that the town that grew up around it became known as Ironbridge.

Ironbridge, Coalbrookdale, Shropshire, opened 1779.

Tom Paine's interest was sparked, and, being of a practical nature, he would have understood that the new iron bridge was based on a sequence of five ribs forming a semicircle, and that the semicircle was known throughout history to be a secure, strong and stable way of bridging a gap. Ever since Roman times the semicircle was used, be it for the vault of a roof or as a bridge over a river. The use of iron was essentially a new and stronger yet lighter method of creating an arch, more convenient and less labour intensive than the vast quantities of heavy stone that had previously been used.

However, the main drawback of a semicircle is that the width determines the height. That is, the wider the gap, the higher the arch would be, making it lack flexibility. It could work in steep gorges like the Severn Gorge where the roadway was high up, but most often it would result in an unpractically high arch, creating a hump-back bridge difficult for horses and carts to get over.

The solution used by the Romans and most bridge builders of the medieval and renaissance period was to use a sequence of small arches crossing a river step by step. This was fine, but clumsy and too many small arches, each needing footings built into the river bed, was both an enormous amount of work and could restrict the flow of the river, as happened with the old London Bridge, which had no less than nineteen arches to get across the River Thames.

There was a need to create a method of spanning wider gaps with fewer individual arches. The first step towards this ambition was taken by the Italian Renaissance architect Bartolomeo Ammannati (1511 - 1592) who, with an artistic flourish worthy of a great mannerist, built the Ponte Santa Trinita in Florence (1567 - 1569), which used just three low elliptic arches to cross the River Arno and which was the first of its kind in the world. Built of stone, it was a remarkable achievement and pushed the boundaries of what could be constructed with stone.

Ponte Santa Trinita, Florence, 1567-1569, by Bartolomeo Ammannati. Rebuilt after being destroyed during the Second World War.

Photo by Sailko, Wikimedia Commons.

However, Ammannati's bridge was a once off act of creative genius, of artistic insight, and was designed in response to a particular situation. It was so far ahead of its time that it was never going to be a formula that could be reproduced in different situations around the world.

The new material that emerged during the eighteenth century, cast and wrought iron, suddenly opened up the possibility of a more rational and ambitious approach to bridge building. For the first time consideration could be given to spanning wide rivers with a single arch.

Tom Paine's idea, which he evolved during the 1780s, was to adopt the new material, iron, but to go back to the arch based on a stable circular form, and at the same time somehow give it the flexibility to be made bigger or smaller, wider or narrower, higher or lower, as required by the geography of the location, without the height being predetermined, as it would be with a semicircle. The solution was, he claimed, based on his observation of a spider's web, a form derived directly from nature. He was keen on the fundamental structures of nature being the basis for our own human efforts at construction.

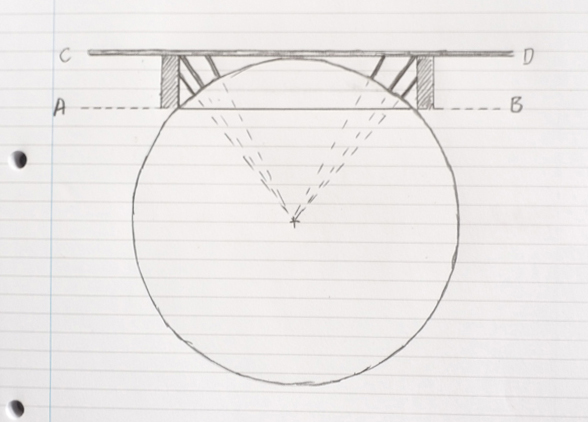

Taking one section of a spider's web was like taking a small section across a circle, called in geometry a cord. The bridge could be based on that cord. The starting point is to draw a large imaginary circle, then draw a cord across a section of the circle that matches the width of the river or gap one wishes to bridge. In the drawing below the cord is marked A-B. The arc of the circle above the cord becomes the arch of the bridge, and the roadway, marked C-D in the drawing, can be placed on top. Any supporting struts can be placed as radiuses, pointing towards the centre of the original circle, making the structure very stable.

Sketch of Tom Paine's bridge idea.

The key point is that the size of the circle can be infinitely varied according to the width of the gap being bridged. Also, the exact position of the cord (A-B) can be moved up or down so that there is a degree of flexibility and scope to match the width with the required height. This means that a formula could be used to construct bridges over a wide variety of situations. His insight would today be called an algorithm with universal applications.

Tom Paine was so keen on his idea that in 1788 he took out a patent on it, which was granted on 26th August 1788 as patent No. 1667. (See Appendix 1.) This was aimed at constructing a bridge over the River Don in Yorkshire, but although he was awarded the patent, nothing happened about actually building the bridge. Paine was not a modest man, some considered him an egoist, so he did publicise his ideas widely and gained the approval of people like Thomas Jefferson, who wrote warmly about the merits of the bridge. Paine even wrote to George Washington about it, but he still lacked evidence that his concept really worked on the ground and it was getting hard to obtain funding.

In order to demonstrate the concept of his bridge, he decided to make a large model, made of iron and over 100 feet wide, which would be open to the public to view for an admission fee. The location he chose was at Lisson Green, a road junction at the edge of Paddington, north west of London. Here there was a well known pub called The Yorkshire Stingo, which had a bowing green and fields around it, giving the space he needed for the display of his bridge.

Drawing of The Yorkshire Stingo.

© Westminster City Archive, London.

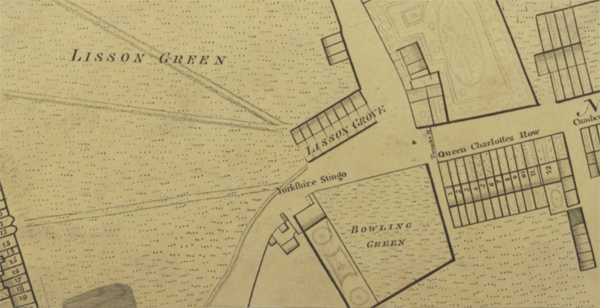

In 1790 he moved into the Yorkshire Stingo and there constructed his model bridge. So far as we know it was on the Bowling Green behind the tavern, seen in the map below.

Horwood's Plan of London, 1799, showing the Yorkshire Stingo and the Bowling Green behind it.

The iron components were manufactured by Thomas Walker of Rotherham, and transported by ship to London. Having already attempted to sell his bridge idea in England, New York and Paris, all without success, this model in Marylebonecould have been of great importance because it could demonstrate the viability and solidity of his idea and gain the interest of the authorities.

However, although people were interested in the bridge, there was no real response in terms of money or investment. After a year the bridge was getting rusty and needed to be dismantled. It is believed that the components were sold to Thomas Walker, the iron manufacturer in Rotherham, and sent north to become part of the new Wearmouth Bridge in Sunderland, which was the second iron bridge to be built in Britain. When it was opened in 1796 it was the widest single span bridge in the world.

Design for Wearmouth Bridge in Sunderland, attributed to Thomas Paine. Ink and Watercolour, 1791.

Courtesy of the Trustees of Sir John Soane's Museum. Photo: Ardon Bar-Hama.

Here below is a sketch of the Wearmouth Bridge by J.M.W. Turner in 1817.

Wearmouth Bridge by J.M.W. Turner, 1817.

© Tate Britain, London.

The fact that Turner, the most highly regarded artist in Britain, chose to visit the site and sketch the bridge indicates how noteworthy and revolutionary it was considered to be. Here below is a later nineteenth-century photograph of the Wearmouth Bridge, capturing what is possibly the clearest photographic expression ever recorded of Tom Paine's idea. Tom did not see the bridge being built and did not get any credit for it, all of which went to local worthies, the iron manufacturer Thomas Walker and Rowland Burdon, the local MP.

Wearmouth Bridge, Sunderland.

This bridge was demolished in 1929 and replaced with the present bridge.

© Courtesy of HES (Sir William Arrol Collection)

One thing to notice is that the Turner drawing shows a distinct hump back to the bridge, which is not present in the photograph. Also, Turner shows circular elements in the spandrels between the roadway and the arch, similar to the circular elements that can be seen at Ironbridge, which are not present in the photograph. These changes happened between 1857 and 1859 when Robert Stephenson (1803 - 1859) was commissioned to strengthen the bridge, which had become weak and unsecure. Stephenson raised the parapets at each side so that the roadway could become flat, and replaced the iron circles with a more dense lattice of girders

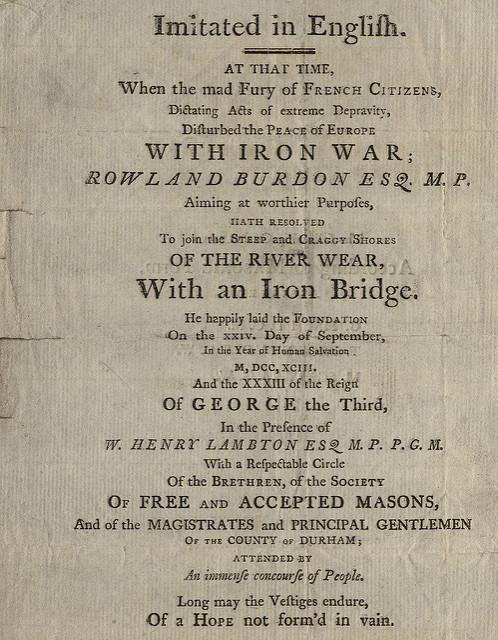

There was a great jingoistic outburst about this bridge, telling the French and all of us how superior we were with our strong iron work. Here is a startling notice about the laying of the foundation stone in 1793, attended by "An immense concourse of People". (Think Donald Trump!)

Laying of the Foundation Stone of Wearmouth Bridge, Sunderland, 1793.

I'm not sure of how Tom Paine would have reacted to such a notice, but it does look like a reactionary hijack of his idea. It is said that by the time the Wearmouth bridge was built, in 1796, he had lost interest in it, but it might have been a case of walking away from something he had not been involved with.

Moreover, he had more serious things to think about. In the year 1793, he was in Paris and in prison and on the verge of being sent to the guillotine. His line of escape was to claim US citizenship, and his bridge building ambitions became centered on America.

In America he cast around for every possible use of his bridge. One option was a bridge over the Harlem River in New York, which would link Harlem with Manhatten. It would have been a huge 300 foot single span bridge made of timber, the point being that his concept could be made of wood or iron as the situation needed. But although a crossing of the Harlem River was desirable, nothing happened in terms of finance and actual building.

His next project was to span the 400-foot-wide Schuylkill River in Philadelphia, which would have been made of iron. But the cost was too great and this project also came to nothing.

However, there is one bridge in the United States that embodies Tom Paine's idea. It is the Dunlap Creek Bridge in Pennsylvania, which stands as the first cast iron arch bridge in America, built between 1836 and 1839, long after Tom Paine's death. Unfortunately it is somewhat overwhelmed by modern intrusions, but the original arch can be seen in the photo below.

Dunlap Creek Bridge

Appendix 1.

A.D. 1788 . . . . No 1667.

Constructing Arches, Vaulted Roofs, and Ceilings.

TO ALL TO WHOM THESE PRESENTS SHALL COME, I, THOMAS PAINE, send greeting.

WHEREAS His most Excellent Majesty King George the Third, by His Letters Patent under the Great Seal of Great Britain, bearing date the Twenty-sixth day of August, in the Twenty-eighth year of His reign, did give unto me, the said Thomas Paine, His special licence that I, the said Thomas Paine, during the term of fourteen years therein expressed, should and lawfully might make, use, exercise, and vend, within England, Wales, and Town of Berwick-upon-Tweed, my Invention of “A METHOD OF CONSTRUCTING OF ARCHES, VAULTED ROOFS, AND CIELINGS, EITHER IN IRON OR WOOD, ON PRINCIPLES NEW AND DIFFERENT TO ANYTHING HITHERTO PRACTICED, BY MEANS OF WHICH CONSTRUCTION ARCHES, VAULTED ROOFS, AND CIELINGS MAY BE ERECTED TO THE EXTENT OF SEVERAL HUNDRED FEET BEYOND WHAT CAN BE PERFORMED IN THE PRESENT PRACTICE OF ARCHITECTURE;” in which said Letters Patent there is contained a proviso obliging me, the said Thomas Paine, to cause a particular description of the nature of my said Invention, and in what manner the same is to be performed, by an instrument in writing under my hand and seal, to be inrolled in His Majesty’s High Court of Chancery within one calendar month next and immediately after the date of the said recited Letters Patent, as in and by the same (relation being thereunto had) may more fully and at large appear.

NOW KNOW YE, that in compliance with the said proviso, I, the said Thomas Paine, do hereby declare that my said Invention of A Method of Constructing of Arches, Vaulted Roofs, and Cielings, either in Iron or Wood, on Principles New and Different to anything hitherto practiced, by means of which Construction, Arches, Vaulted Roofs, and Cielings may be Erected to the Extent of several Hundred Feet beyond what can be performed in the present practice of Architecture, is described in manner following (that is to say):—

The idea and construction of this arch is taken from the figure of a spider’s circular web, of which it resembles a section, and from a conviction that when nature empowered this insect to make a web she also instructed her in the strongest mechanical method of constructing it.

Another idea, taken from nature in the construction of this arch, is that of increasing the strength of matter by dividing and combining it, and thereby causing it to act over a larger space than it would occupy in a solid state, as is seen in the quills of birds, bones of animals, reeds, canes, etc. The curved bars of the arch are composed of pieces of any length joined together to the whole extent of the arch, and take curveture by bending. Those curves, to any number, height, or thickness, as the extent of the arch may require, are raised concentrically one above another, and separated, when the extent of the arch requires it, by the interposition of blocks, tubes, or pins, and the whole bolted close and fast together (the direction of the radius is the best) through the whole thickness of the arch, the bolts being made fast by a head pin or screw at each end of them. This connection forms one arched rib, and the number of ribs to be used is in proportion to the breadth and extent of the arch, and those separate ribs are also combined and braced together by bars passing ’cross all the ribs, and made fast thereto above and below, and as often wherever the arch, from its extent, depth, and breadth, requires. When this arch is to be applied to the purpose of a bridge, which requires more arches than one, they are to be connected in the following manner (that is to say):—Wood piles are to be driven into the earth; over each of those piles are to be let fall a hollow iron or metal case, with a broad foot let into a bed; the interspace between the case and the wood pile to be filled up with a cement and pinned together. The whole number of those pillars are to be braced together, and formed into a platform for receiving and connecting the arches. The interspaces of those pillars may be filled with plates of iron or lattice work so as to resemble a pier, or left open so as to resemble a colonade of any of the orders of architecture. Among the advantages of this construction is that of rendering the construction of bridges into a portable manufacture, as the bars and parts of which it is composed need not be longer or larger than is convenient to be stowed in a vessel, boat, or waggon, and that with as much compactness as iron or timber is transported to or from Great Britain; and a bridge of any extent upon this construction may be manufactured in Great Britain and sent to any part of the world to be erected. For the purpose of preserving the iron from dust it is to be varnished over with a coat of melted glass. It ought to be observed, that extreme simplicity, though striking to the view, is difficult to be conceived from description, although such description exactly accords, upon inspection, with the thing described. A practicable method of constructing arches to several hundred feet span, with a small elevation, is the desideratum of bridge architecture, and it is the principle and practicability of constructing and connecting such arches so as totally to remove or effectually lessen the danger and inconvenience of obstructing the channell of rivers, together with that of adding a new and important manufacture to the iron works of the nation, capable of transportation and exportation, that is herein described. When this arch is to be applied to the purpose of a roof and ceiling cords may be added to the arch to supply the want of butments, which are to be braced to or connected with the arch by perpendiculars.

In witness whereof, I, the said Thomas Paine, have here-unto set my hand and seal, the Twenty-fifth day of September, in the year of our Lord One thousand seven hundred and eighty-eight.

THOMAS (L.S.) PAINE.

Sealed and delivered, being first duly

stamped, in the presence of

PETER WHITESIDE.

AND BE IT REMEMBERED, that on the Twenty-fifth day of September,

in the twenty-eighth year of the reign of His Majesty King George

the Third, the said Thomas Paine came before our said Lord the King

in His Chancery, and acknowledged the Instrument aforesaid, and all

and every thing therein contained and specified, in form above

written. And also the Instrument aforesaid was stamped according to

the tenor of the several Statutes made in the sixth year of the

reign of the late King and Queen William and Mary of England, and so

forth, and in the seventeenth and twenty-third years of the reign of

His Majesty King George the Third.

MONTAGU.

Inrolled the said Twenty-fifth day of September, in the year

last above written.

From http://www.bartleby.com/184/209.html

Further Reading:

https://greatwen.com/2011/07/18/thomas-paines-london-bridge/

http://www.vqronline.org/essay/thomas-paine-bridge-builder

http://www.innovationgateway.org/content/tom-paine%E2%80%99s-bridge-1?page=show

Edward G. Grey, Tom Paine's Iron Bridge: Building a United States.

W. W. Norton & Company, 25 Apr 2016.